At the dawn of the Twentieth Century, residents of Sherman, Denison and the surrounding areas were hard pressed to find ways to escape blistering summer temperatures. It was a time when the heat of a Texas summer slowed life to a crawl and in the evenings grownups sat on front porches hoping to catch a cooling breeze, while watching children chase lightning bugs.

Air conditioning in homes, offices and businesses lay decades in the future. Lake Texoma was nearly half a century over the horizon. Air conditioned shopping malls could not have been imagined.

Tall shade trees and water offered the only escape from the temperatures that annually baked Texas in July and August. Since Texas has only one natural lake, Caddo Lake in East Texas, both governments and individuals found ways to dam up creeks and streams to create larger bodies of water to offer cooling escapes from the searing summer temperatures.

J.P. Crearer’s Interurban Promotion

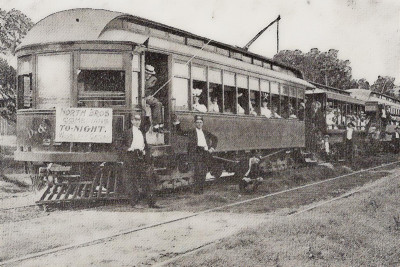

In 1901, Denison businessman J. P. Crearer, an entrepreneur looking for a way to attract riders to his recently completed ten-mile long electric interurban rail line connecting Sherman and Denison, needed a gimmick to lure people onto his new-fangled people mover. He found it in an artificially created lake that over the course of several decades would attract thousands upon thousands to its shores.

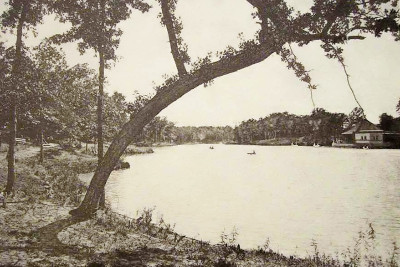

Halfway between Denison and Sherman was Tanyard Springs, an area heavily wooded with elms, oaks and hickories and containing a flowing spring. Crearer built a dam below the springs, creating a small lake—one that not only provided water for a power plant to generate electricity for his rail line—but more importantly creating a recreational destination to lure paying customers onto his interurban, the first in the state of Texas.

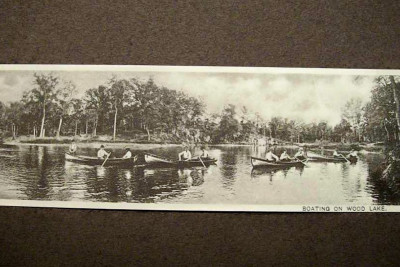

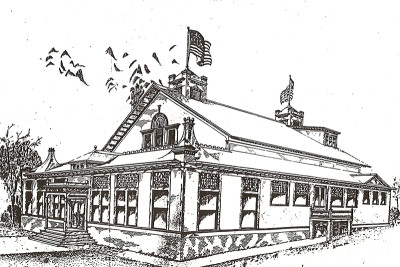

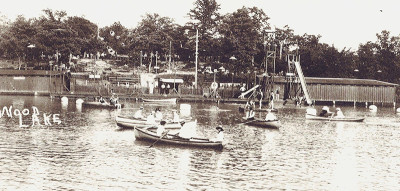

Crearer called the development Woodlake, and over the next two decades, it flourished as a popular summer retreat for Grayson County residents, as well as for tourists throughout north central Texas and southern Oklahoma. In its heyday, the forty acre resort and recreational park offered visitors a myriad of attractions and activities, including boating, swimming, a flume, fishing, picnic grounds, a zoo, carnival rides, a baseball diamond, a palatial Victorian casino, an open-air dance pavilion and a penny arcade that was sometimes used for roller skating.

What Woodlake was like during its first two decades can be gleaned from published reports or oral history tapes at the Sherman Public Library. And from those long ago accounts, it was a grand place indeed.

It was an idyllic time that generated a lifetime of memories: family picnics with plenty of fried chicken, barefooted youngsters dipping their toes in the cooling waters of the lake, fishing corks bobbing peacefully on the tranquil surface of the serene oasis and nature’s canvas blooming with roses, crepe myrtles and magnolias. Away from the crowds, young lovers strolled underneath the stately trees, stealing a kiss or two before returning to the more public activities of the Woodlake attractions.

Do you have memories of Woodlake? Share your remembrances with our readers by posting a comment. Have a question we didn’t answer? Writer Gene Lenore will respond.

All Aboard for Woodlake

In Denison, passengers boarded the train at the Woodard Street depot. Sherman residents stepped aboard at the company’s downtown headquarters at the corner of Lamar and Travis. A round-trip for the five-and-a-half mile ride to and from the Woodlake Station cost fifteen cents. The trains left hourly from both Sherman and Denison for Woodlake starting at 7 a.m. and ending at 11 p.m.

Powered by overhead electric lines carrying six hundred volts of direct current, the trolley cars shot down the tracks at forty mph, lurching and swaying their way across the countryside, eventually earning the coaches the nickname of “Leaping Lenas.”

Men arrived at Woodlake dressed in suits, ties and straw hats. Fashionable women of the day wore ankle-length white dresses with long sleeves, long gloves, hats and high button shoes. For a dip in the lake, the men changed into knee-length tank suits and women into bloomers, long stockings and rubber shoes.

The enclosed swimming area known as “The Pig Pen” featured a wooden floor and rails. Lifeguards kept an eye on swimmers from a three-tiered tower. For the more adventurous, there was a “chute the chute” where screaming passengers in canoes slid down a steep wooden flume into the lake below.

Boats could be rented for twenty-five cents an hour. Spirited boat races between teams from Sherman and Denison drew cheers and applause from the crowds as they rooted for the home teams.

A Grand Casino, Long Before Choctaw

The most famous attraction at Woodlake was the Casino, a palatial Victorian-style opera house featuring velvet sofas and stained glass windows. The opulent two-story, twenty-thousand square foot structure overlooked the lake and during the summer months there was room for nine-hundred people to see a variety of entertainment on the Casino’s huge stage—vaudeville shows, musicals, minstrel shows, high school productions, and occasionally a newer form of entertainment rapidly growing in popularity—motion pictures.

In 1915, a short distance southeast of the Casino, the park opened an open-air dance pavilion, which offered live music on Friday and Saturday nights. Orchestras like the Woodman Band of Sherman entertained the dancers with popular songs of the era, such as “Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby,” “Ain’t We Got Fun,” and “When It’s Springtime in the Rockies.”

In 1908, Woodlake and Crearer’s Denison and Sherman Interurban rail line were sold to the Texas Traction Company, which had constructed an interurban line from Dallas to McKinney. During the heyday of the interurban, Grayson County residents could ride interconnecting interurban lines as far south as Waco, as far west as Fort Worth and as far east as Terrell.

In 1918, the Woodlake operation was sold to the Texas Electric Railway Company. Over the next decade, the fortunes of Woodlake began a decline from which they would never recover.

Several factors killed Woodlake as a popular recreation destination, including a series of tragic interurban accidents that resulted in death and injuries, the growth of the motion picture industry, the birth of radio as an entertainment medium and the rise of America’s automobile culture.

By 1929, the Woodlake grounds were unkempt, and the once grand buildings were rapidly losing their luster. Texas Electric officials closed the park, tore down the Casino and shipped the lumber out of Grayson County to be used for the construction of Interurban depots between Fort Worth and Waco.

But Woodlake would not slip quietly back to nature. In that same year, a small group of Grayson County residents banded together, pooled their resources, organized a venture known as Woodlake, Inc., and purchased the property for private use.

Holding On to the Past, Preserving for the Future

Sherman attorney Robert Minshew is the current president of the non-profit Woodlake, Inc., a position he inherited from his sister Betty Mitchell, who served in the position for more than twenty years.

Minshew said the group that purchased the property “wanted to preserve an important piece of Grayson County history.” He said the people that bought the property, as America was heading into the Great Depression, wanted to keep the beautiful place intact. “They did not want to see the property broken up for private development,” he added.

Before long, members of Woodlake, Inc., began constructing private cottages at the lake for their own use. The cabins became gathering places for family and friends, and the cooling waters of the lake helped float childhood memories for those who grew up there in the 1940s and 50s.

Mitchell remembered how she learned to swim in Woodlake’s “Pig Pen,” which by the mid-1940s had lost much of its character. She recalled how slime and moss covered the bottom planks and how some of the planks had rotted away. “I learned to swim because I was afraid I would fall down into the cracks and never be found,” she said.

Through the next three decades, these private cottages became variously both homes for permanent residents and weekend retreats for property owners, and until the Interurban stopped running, residents and property owners could still catch a ride to Woodlake on the trolley.

Mitchell remembered how she and her mother and brother would board the Interurban at Walnut and Brockett in Sherman to ride to Woodlake. “We would go out there on family picnics and holidays and swim and fish. There was always plenty of fried chicken and potato salad,” she said.

By the late 1960s, the last permanent resident moved from Woodlake, and it became a place where property owners could find solitude and spiritual renewal in the sounds of nature.

Mitchell said that until a new road was cut along the south end of the lake a couple of years ago, making the lake visible from the road, it was like being in paradise. “You were out there alone, just you and God and nature. We’ve left it natural. We haven’t modernized anything,” she said.

Over the years, starting in 1921 and continuing through 1954, summertime at Woodlake also meant the influx of thousands of young Baptists who converged on the site for religious retreats. At one point, the old dance pavilion was converted to a girl’s dormitory and the original Interurban station into a cafeteria. Not far from the pavilion, an open air tabernacle was built for church services.

The Interurban made its last trip to Woodlake in 1948, two years shy of the opening of North Central Expressway, linking downtown Dallas with Richardson, Plano, Allen and McKinney.

The two-story red-brick building that housed the electric dynamos now has no roof. The walls are crumbling, and the glass has disappeared from the arched windows. Brick walkways disappear into dense brush. Concrete steps at the site of the former “Pig Pen” vanish into the calm waters of the lake.

Scattered about the property today are visual reminders of Woodlake’s golden age. The dilapidated dance pavilion appears as a sentinel standing guard over what once was and what will never be again.

My family was one of the permanent residents at Woodlake in the 50s. My Dad along with many others did so much to maintain the beautiful park that was still there. Woodlake was a great place in the summer with many of the cottage people and camps coming to the area. Beautiful memories, and I still go out there when I come to the town. Since I no longer have access to the lake it is impossible to walk the grounds. It must have been such a show place in its early days.

I’m embarking on a project to capture this time in Sherman’s history. I would love to contact the current owners of Woodlake and request permission to photograph the property as it is now. I was recently granted permission to photograph the Woodmen Circle Home. Please let me know if there is a way to contact the owners or if you could pass this along to them. Thank you for any help you can provide.

Ive had an interest in Woodlake, since i was just a lil child. My gr8 grandparents owned a cabin there and if i understand correctly, he died there.I would love to see the place, to even take some pictures for my children & grandchildren. Woodlake, holds so many memories for so many ppl… it must have been very beautiful in its hay day. I know access is denied but, would love a tour, if there offered. Or even to know where it is exactly.I do not however understand all the secrecy about Woodlake!

Woodlake is privately owned and access is restricted. But you can see the lake using Google Maps satellite view. You’ll see it to the west of Woodlake Road, just north of the Woodlawn Country Club.

Can you give me directions to Woodlake, I would love to go there and take pictures.

Thank You