This article appeared in the Summer 2008 issue of Texoma Living!.

Over four generations, the Nuckols clan moved west from Virginia to new farms. But all that changed when Virgil Nuckols encountered the cowboy myth in late 19th Century Texas. He was transformed from a farmer to the Texas Kidd. The cowboy myth was propagated by the dime novel and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West [show]. Later, the Western movie spread the myth worldwide. Texas Kidd’s Reproduction of Frontier Days had the distinction of being the last of the Wild West shows. Tom Nuckols grew up on the Wild West show, but neither he or any of his generation of Nuckols continued this life style. Instead, they were transformed from cowboys to urban Texans, who turned to knowledge and technology for a livelihood, not the horse and land.

“The Texas Kidd,” if that don’t conjure up visions of Buffalo Bill and Tom Mix, thundering herds of fire-breathing longhorns on the stampede, strong-willed cowboys, daring and beautiful cowgirls, prancing horses and boundless excitement, then you haven’t lived. Say “Texas Kidd” to Tom Nuckols, and he’ll remember those days. Remember them, heck partner, he was the Texas Kidd, or at least he would have been.

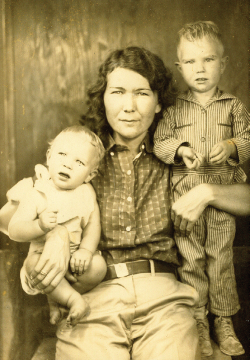

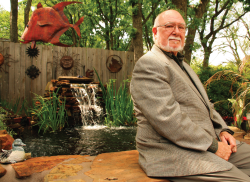

Tom Nuckols, Austin College emeritus professor of religion, ordained Baptist minister, former naval aviator, legal officer, and chaplain, could have become Texas Kidd III and the impresario of a Wild West Show. His father, Reno Nuckols, was Texas Kidd Jr., a star performer in the family-owned traveling show, which was on the road in Louise, Texas, in 1933 when Tom was born in a trailer. Like his father, the boy traveled with the show as a child. He received his first three years of education from a different teacher each week, as the show moved from town to town.

By the time Nuckols entered Tulane University, he had worked in the “joints” (concessions) and coped with such crises as a stalled Ferris wheel loaded with riders and a “Hey, Rube” knife fight that left him wounded. No doubt his experiences as an “outsider,” on the margins of society, helped him choose to study politics and teach Christian ethics.

When Tom’s father married Flo Brazzel, who rode bucking horses in the show, his father gave them the carny’s version of a shivaree. Around closing time, he got the couple on the Ferris wheel by themselves, stopped it with the newlyweds at the top, and kept them there for a lengthy and embarrassing serenade by friends and coworkers.

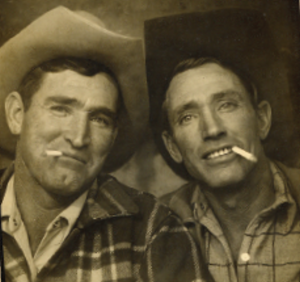

In the 1800s the Nuckols family had emigrated to Midlothian, Texas, from a blackland farm in Alabama. While a youngster, Virgil Nuckols, Reno’s father, Tom’s grandfather, embraced the cowboy lifestyle and became a successful horse trader. Riding bucking horses and training them for cowboys who worked cattle was what he did every day. But that wasn’t half as exciting as putting on the “reproduction of frontier days” and playing the Texas Kidd. There were plenty of cowboys to play supporting roles, and his two sons and a son-in-law were happy to join the cast of characters. During the Great Depression, the show supported as many as 150 performers and family members.

The Texas Kidd show had big boots to fill when it began in 1917. That was the year that Buffalo Bill Cody died. He had started his Wild West (he never used the term “show”) in Wyoming in 1883, and, according to Larry McMurtry, it brought him wealth and also made him the most recognizable celebrity on earth. Not content with touring this country, Bill went to England for Queen Victoria’s Jubilee in 1887, taking along sharpshooter Little Annie Oakley and Chief Sitting Bull, among others. Two years later, they toured continental Europe, meeting Pope Leo XIII, as well as more kings and queens. World War I ended Bill’s touring days.

When Virgil Nuckols started his show, he had no idea that his sons Reno and Grafton (Baby) and their descendants would still be performing it more than forty years later. Being a shrewd entrepreneur, Virgil saw a way to give his enterprise a distinctive title when he encountered another showman who sold him a supply of handbills advertising “The Texas Kidd.” Overnight, Nuckols assumed a colorful new identity, and his show became “Texas Kidd’s Reproduction of Frontier Days.” When they “tore down” for the last time in 1958, the Texas Kidd show was the last of the species.

In developing his show, Nuckols began with Cody’s model: a mix of frontier spectacle, feats of showmanship, sharpshooting, and rodeo style events. As a boy, Virgil’s oldest son, Reno, learned rope tricks and then became adept as a bronco rider. After performing in rodeos at Madison Square Garden several times as Texas Kidd Jr., he became one of the founding members of the union for rodeo performers, the Cowboys’ Turtle Association. (The cowboys chose that name because, while they were slow to organize, when push finally came to shove, they weren’t afraid to stick their necks out to get what they wanted.) Today, the union is the Professional Rodeo Cowboy Association.

The Texas Kidd show had black as well as white cowboys, but it gave star billing to a Mexican family, the Alvarados. As they and their sons provided most of the trick roping, the parents were among the elite handful addressed as “Mr.” and “Mrs.” Virgil’s wife, Mornie Lou Nuckols, was called “Miz Tex,” and she became known across the state by that nickname.

The only other “Mr.” was the advance man, a shrewd negotiator who also served as the “patch” to fix problems with local law enforcement or unhappy customers. The cowboys had colorful stage names: Montana Red, Dare Devil Pete, Crazy Dan. The bucking horses had names like Midnight, Black Diamond, Knox City, Salty Dog and High Roller.

Cowboys were easy to find, but some of the animals were unique. In the 1920s, when longhorn cattle were almost extinct, the Texas Kidd show acquired two steers with horns that measured six feet tip to tip. They named them Kalamazoo and Yellowjacket. When first acquired, the animals were so wild they had to be hemmed in by a horse and rider on each side, with two lariats on their horns. They became family pets, and to advertise the show, Texas Kidd would drive one of the steers through town in a trailer and use a loudspeaker inviting onlookers to draw near and get a taste of the wonders of the Wild West.

Tom Nuckols recalls with great affection one bucking cow, a Brahman (pronounced “Bremmer”) they called “Sally Rand,” after the fan dancer who became famous at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. The cow was almost impossible to ride, Nuckols said, because she could “really shake it,” like her namesake. Mated with the show’s Brahman bull, “Walter Winchell,” she produced a calf each year. Her offspring added a lot to the show, because the cowboys trained them to become just as ornery as their parents.

Another valuable performer was a small, black, deceptively meek looking Spanish mule named January. Texas Kidd offered $100 to anyone who could ride her and never had to pay off. “She would rise up on her hind legs to become almost vertical, and she could also ripple her skin to dislodge a would-be rider who tried to lock his legs around her belly,” Nuckols explained. Many came to the show convinced they could claim the purse, but January always sent them flying.

Changes in modes of transportation were keys to the evolution of the show. Early photos show how the troupe set up tents and stretched tarpaulins from the show’s wagons to provide a backdrop for their performances. They slept on bedrolls and cooked meals over a campfire. For a brief period during the 1920s, the Nuckols show teamed up with big carnivals that toured the Midwest by rail, but that didn’t bring in enough money. So it was back to touring Texas, except by then they had “house cars,” custom built of wood on a truck chassis and covered with sheet metal painted to depict rodeo scenes.

“These were like small versions of today’s RVs, and they also served as mobile billboards.” Next came homemade small trailer houses, which gradually increased in size to offer more amenities. The height of luxury came along after WWII, when Reno Nuckols purchased a “Spartan Mansion,” an expensive 33-foot trailer made entirely of aircraft aluminum by J. Paul Getty’s Spartan Aircraft Company.

During the worst years of the Great Depression, the show kept the Nuckols’ extended family and as many as 150 performers fed and clothed. When the show made money, they got new clothes and boots, and there were plenty of cowboys willing to work for food and clothing (plus tobacco) during the 1920s and ‘30s.

Each year the troupe followed a regular circuit around the state, as the cotton crop cycle—chopping in spring, harvesting in summer—put money in the jeans of rural and small town workers. The work schedule was relentless: move to a new location every Sunday, have carnival “joints” ready to open nightly by 6:00, be prepared for late hours on Friday and Saturday, tear down after midnight on Saturday. If the new location had a movie house with Sunday night picture shows, that was the only opportunity the workers had for a little entertainment for themselves.

The troupe couldn’t afford a winter break, so they would work their way along the balmy Gulf Coast and the Rio Grande Valley. They didn’t bring in much, and occasionally, after two weeks in the same town, the locals might take up a collection for gas money to get them moving again. When there wasn’t enough money to get current license plates, the show moved only at night.

By 1940, there were often as many as 12 to 15 children of school age traveling with the show, and each one had a little book indicating what grade the child was in, with progress notes written by each teacher for the benefit of the next. Nuckols still has one of his books, with comments like, “He does pretty well, considering what little chance he has.” Creative teachers would use the visitors to instruct their students about a different way of life, while others resented them as a disruption. Teachers’ written comments told more about themselves than about the pupils.

World War II brought a temporary halt to the shows, as the draft took most of the cowboys and gas rationing restricted travel. In 1948, Reno and Grafton Nuckols began touring again with the combination carnival and Wild West show, but the 1950s offered new challenges: state excise taxes on ticket sales reduced profits, and TV offered Americans varied entertainment in their living rooms. In 1958, the Texas Kidd show stopped performing.

Tom Nuckols had decided years earlier that he had no desire to pursue a career as Texas Kidd III. “When I was a child, it became evident that ideas and words interested me more,” he said. He recalls one occasion when there was a shortage of cowboys, and he attempted to ride the bucking cow, Sally Rand. “She threw me quickly, and I didn’t follow Texas Kidd’s advice. I made a painful three-point landing. Being a teenager, my first thought was, ‘How will this affect my playing basketball?’” Showmanship was hardly a priority.

Then there was the Ferris wheel incident. From his father, he learned how to set up, tear down, and operate the big wheel, which had a cable-driven mechanism that would malfunction if the load of riders wasn’t properly distributed. Nuckols was present when a locked-up Ferris wheel caused the worst accident the show ever had. “Loaded with passengers, it froze and then rocked, and some of them began to scream. My father used ropes to rotate the wheel slowly, and all of them were rescued. It took a long time, and all of us were anxious. Of course, we tore down and left immediately. Nobody in that town would get back on the wheel.”

Nuckols was not given to violence, but when a fight between carnies and rubes broke out, he didn’t hold back, stepping in to save his father from a knife in the back. He saw a man approaching his father from behind with a long knife and ran to grab him. He got a cut on his arm that left him with a scar that he still carries. The melee ended when two sheriff’s deputies waded into the crowd with guns drawn and began cracking heads. The incident took place in the 50s when few people carried guns, so no shots were fired, but the Texas Kidd show left town overnight all the same.

Instead of riding bucking horses, Tom Nuckols felt a calling to study politics, religion and ethics. After graduating from Tulane University in New Orleans with a Naval ROTC commission, he became a naval aviator and a hurricane hunter in the Gulf of Mexico. He followed up his naval career by accepting a Rockefeller Fellowship to attend Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

College teaching looked more attractive than the ministry, and Nuckols won a prestigious Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship for graduate study at Duke University. While earning his Ph.D. in religion, he accepted a position at Austin College in 1965 and remained there until he retired in 1998. Christian ethics was his specialty.

One influence from his childhood remains strong: traveling. He can be ready to go on short notice. Risking a venture that few Texans would undertake these days, recently he and his brother Bebe drove themselves clear across Mexico to Belize and back. “It was just one more road trip for us.”

To LAVINIA TRULL,

Yes, Rovella lived in Pine Bluff, Arkansas.

I know her brother, Earl (Red) Beadle, who was also in the rodeos.

Rovella died from lung cancer about 12 years ago.

Earl has told me many stories about those days. Must have been thrilling times.

IN THE MIDDLE FIFTIES I KNEW TEXAS KID JR & HIS WIFE ROVELLA, WHO WAS A BARREL RACER. I’VE OFTEN WONDERED WHAT HAS HAPPENED TO THEM. ROVELLA WAS FROM ARK. SHE WAS YOUNGER THAN KID. WOULD LIKE TO KNOW WHERE THEY ARE. HE HAD A PLACE JUST SOUTH OF FT WORTH JUST OFF 35 THAT U COULD SEE FROM THE HWY. ALL THE TRUCKS, TRAILERS, ETC., WERE THERE.

My brother, Bill Lewis joined the Texas Kid Wild West Show in the mid 1940’s. Bill was a bronc rider and worked for Grafton Nukols.

My dad was a cowboy with the Texas Kid wild west show, he would have been there in the early 50s. His name was Edward, but was known as Billy Reno in the rodeo arena. He said he learned how to ride from Babe and Sally Rand was his teacher. He had many fond memories and great stories of his time with Babe and Reno. He lost many photos of his youth in a hurricane on the coast. He was from around Bay City.

Tom:

After my comment before I have found an advance poster or a letterhead advertising The Texas Kidd Show on it . It advertises “carries whites no gaff no fortune tellers, also I mentioned a lady called Smokie could her last name have been Forester? Please feel Free to email me.

Billie S Miller

Tom;

My father was on the Texas Kidd Show. His name was Fred L Wells AKA Tiger Wells or Delmo Wells. He did Australian whip cracking, fire eating, escape artist, the man that couldn’t be hanged act, and Hollywood stunt man. My mother was Billie Wells a rifle and pistol shot. I was very young at the time but remember Texas Kidd called me Sue Bil. I guess it kind of stuck thru the years hence my email address. I also remember a lady bronc rider called Smokie, she tried to talk my parents into letting her adopt me. If you remember any of these please fell free to email me as I was only about 3 or 4 at the time. My father later had his own “Tiger Wells Show”. We also were with Monroe Brothers Circus.

Billie S Miller

Dear Mr. Nuckols,

My mother, who is now 85, use to know Virg Nuckols.At one time he ask her father Earl Russell to take her and make her a bull rider (back in the 30’s) of course grandma said no, I’m sure grandpa being a cowboy himself thought about it. LOL.

Grandpa and his brothers had a small weekend rodeo back in the twenties but not on the scale of the Nuckols’. but they knew each other and would visit each chance they got.

Mother said she remember’s the first time she met Babe, It was during the war and he was on his way to San Diego to work in the ship yards and she said he was one of the tallest men she had ever seen before, he had to bend down to get in the room. LOL.

Then she said that Virg was one of the sweetest men she ever met , she “just loved him”.

She said the last time she say him she was working at a cafe off the highway in Alvarado,Texas and his head was in bad shape, all bandaged up. She kissed him on the side that wasn’t bandaged and that was the last time she saw him, that was about 1949, but she thought of him alot through out the years.

I wish you had photos of my grandfather but I’m sure you don’t and prob. no one would even remember him. but they had a house fire and any photos they had were burned up.

Try Austin College.

Tom,

I have a friend that remembers you as a youngster. His sister, Rovella, was married to your Dad in the 50’s. You would have known him as Buddy Beadle. He would like to talk with you if possible. He’s told me many stories about your dad. His memory is fantastic and I’m sure you would enjoy speaking with him. If you

would like to contact him e-mail me and I’ll give you his phone number.

i would love to hear more stories of our origins. My name is Virgil G Nuckols IV