This article appeared in the May-June 2009 issue of Texoma Living! Magazine. Photos by Stephen Olner

A Matter of Convenience

Texas can claim as its own the very first modern convenience store chain, 7-Eleven. The idea took root in 1927, when Joe C. Thompson, manager of the Southland Ice Company in Dallas, started selling his ice customers eggs, bread, and milk from the dock where they picked up their ice. There were small groceries and markets in the neighborhood, but people immediately took to the convenience of picking up everyday necessities at the same time they bought the ice needed to preserve them. Even in 1927, quicker and easier was better.

Eight decades later, with untold thousands of convenience stores all over the world, Texas can claim as its own one of the most innovative convenience store chains in the country, perhaps in the world. Most innovative at any rate if a spot in the Convenience Store Hall of Fame, a pair of awards for convenience store of the year, and a dozen or more “firsts” in the business of making it quicker and easier for people to get what they need and get on their way, count for anything.

It is not just a question of convenience, either. The convenience needs to go unnoticed. It needs to be taken for granted by the customer. To that end, good enough is not good enough. To be invisible, things need to be perfect.

At noon on a Wednesday, Bill Douglass stops by the Dickey’s Barbecue in his Lone Star Exxon store… he is there to pick up some sandwiches to take to a lunch meeting.

At noon on a Wednesday, Bill Douglass stops by the Dickey’s Barbecue in his Lone Star Exxon store at the corner of US 75 and West Lamar in Sherman. He is there to pick up some sandwiches to take to a lunch meeting.

As he walks in the back door, he greets the people behind the counter by name, and they greet him. He places his order, and while waiting for the sandwiches, he steps down the serving line and meticulously cleans off bits of shredded cheese that have spilled out of the serving pan and onto the stainless steel counter.

With the little bits of cheese cupped in his hand, he walks over to the trash bin and disposes of them. Something else catches his eye and he pulls a napkin out of a dispenser and wipes up a spill by the soft-drink machine. “Good enough” is not good enough for Bill Douglass, whose fifteen-store Lone Star chain has not been on the cutting edge, but has been the cutting edge of the convenience business for more than ten years.

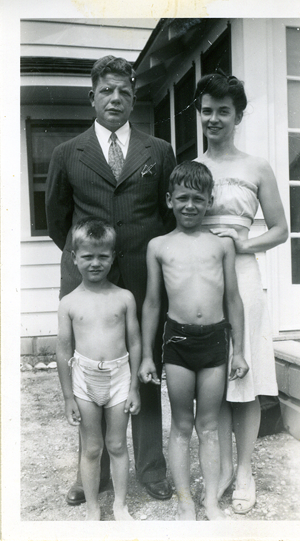

My father was a professional basketball player, William Patterson Douglass. He played for the team in Philadelphia before the NBA came into existence. My mother obviously liked jocks, because when she divorced him when I was only one, she married a professional football player. My stepfather, William Henry Weldon Hitchcock, played for the Frankford Yellow Jackets, although by then, he was working for the telephone company.”

“I was born in Philadelphia, because that was the big medical center, and my mother’s father was a doctor, but we never lived there. We moved a lot. By the sixth grade, I had been to five schools. I was always the new kid, and you always had to fight.”

By the time Douglass reached high school in the late 1940s, the family lived in the small town of Trappe, Pennsylvania. It was near Valley Forge in the country of the Amish and the Pennsylvania Dutch. “My mother was very emotionally unstable and very sickly in the sense that every year she went into a mental institution on her birthday, every spring, just like clockwork.

By the time Douglass reached high school in the late 1940s, the family lived in the small town of Trappe, Pennsylvania. It was near Valley Forge in the country of the Amish and the Pennsylvania Dutch. “My mother was very emotionally unstable and very sickly in the sense that every year she went into a mental institution on her birthday, every spring, just like clockwork.

“I was essentially a kid with a part-time parent and a stepfather who was always kept broke because he took care of her. He would pay to put her in a private institution because the state institutions at that time were pretty barbaric. We were so poor we didn’t have a car. If you don’t have a car in the country, you’re poor.”

Growing up on the edge of the community, without the things other kids have and without a lot of supervision, is not only difficult, it is dangerous…

Growing up on the edge of the community, without the things other kids have and without a lot of supervision, is not only difficult, it is dangerous, and young Bill Douglass was edging toward wrong choices and bad decisions. Then help came along, in the unlikely form of a stern minister of German origin, Reverend Russell W. Zimmerman of the Augustus Lutheran Church in Trappe.

“He decided that if he didn’t take an interest in me, I was going to become incorrigible or worse. He knew what was going on. I was raising myself. My father had to work, and he worked long and hard, and my mother was pretty fragile,” said Douglass. Zimmerman asked the teenager, he was fourteen, to take on a job caring for the church grounds. “It was known as the ‘Oldest Unchanged Lutheran Church in America,’” Douglass recalled. “It was built in 1743.”

The learning process started early with Reverend Zimmerman. “The church had a coal fire, and the first thing I had to do was haul away the ashes, so I asked him how to do it, and he said, ‘You figure it out.’” So Douglass figured it out. He borrowed the sexton’s car, taught himself how to drive it, and hauled the ashes to the dump. It may have been lesson number one on the road to success—“figure it out.”

After that, Zimmerman’s lessons were more down to earth, below the earth actually. “He taught me how to dig the hole you set the headstone in at the graveyard,” Douglass recalled. “There is a way you shape the hole so the frost won’t push [the stones] out of the ground.” Once Douglass had mastered headstones, there was no way to go but down.

“We dug our graves by hand,” he said. “I made eighty cents an hour, which was better than the seventy cents an hour I got mowing the grass. Digging a grave was tough, because as the hole got deeper you had to throw the dirt higher, and they made you throw it into a box because you couldn’t put dirt on other people’s gravesites. When the box got full, they’d put another slat in it, and when you’re down there at five feet and the slats are up to five feet, that’s a long toss, especially if you’re a kid.”

Applying success-lesson number one, Douglass figured out that tossing dirt out of a hole in the ground did not offer much in the way of a future. “It taught me that I had to get an education.” he said. “This was not a way out.”

Douglass worked at the church for two years while the minister worked on him. “He was really my mentor, my father figure. He taught me how to do what you were supposed to do, if that makes sense? He was very precise, very German. If I was due in at two and came in ten minutes late, he would call me in. He said, ‘What you do for me is you show up on time.’” That may have been success-lesson number two.

At sixteen, with a newly-earned driver’s license, Douglass got a job and a raise in pay to a dollar an hour at the newest business in Trappe, a brand new Esso gas station. (Esso was a predecessor of Exxon. On January 1, 1973, Esso, Enco and Humble became Exxon.) With the job came an introduction to a new world of possibilities.

“The sales rep that called on us always came in wearing a tie, a nice sport jacket and a hat. In those days everybody wore a hat. He had a real shiny company car. That car was a big thing in my mind, because we didn’t have a car. Having a car was a big achievement, a status symbol.”

Status symbols usually don’t come easy, and from the rep, Douglass learned that he needed to go to college, get a diploma and get his obligation to Uncle Sam and the Selective Service out of the way before he could apply for a job. “He said, ‘When you get out of the service, you can use me as a reference.’”

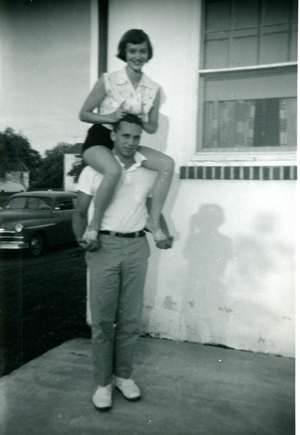

Douglass was now a man, or at least almost a man, with a plan. Along the way he found the time to participate in school events, crack the books enough to finish in the top ten percent of the class at Collegeville-Trappe High School and find a girl to be Queen to his King of Hearts at the big Valentine Dance. The girl was Joan Elizabeth Ledger, and the royal couple have been together ever since.

He was also an athlete, a halfback and linebacker for the Collegeville Colonels, and his play on the football field garnered the attention of Coach Rip Engle at Penn State, who offered Douglass a scholarship. This was playing with the big guys. “Lenny Moore and Roosevelt Grier were in my class,” Douglass remembered. “And the varsity players were so big I couldn’t see over them when we scrimmaged.”

A severe bout with mononucleosis in the middle of his first semester at Penn State ended his football aspirations and his time in the shadow of Mount Nittany. When he recovered, Douglass enrolled at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

The Lutheran school was founded in 1848, and their athletic teams are called the Mules. You’ve got to figure that a college with a mule for a mascot is a pretty “get it done” place, and Bill Douglass was ready to get it done. He had lost a year to illness, and so he doubled up and finished in three.

“Semper Fi”

In the mid 1950s, a yellow light in the career path of American young men was the Selective Service System, the all-but-universal draft. At eighteen you went down to your local draft board, signed up, stuck the draft classification card in your billfold and assumed that sooner or later the letter which opened with “Greetings” would come in the mail. There were no wars, nothing major at least, at the time, but “going in the service” was a common experience. Even Elvis was drafted.

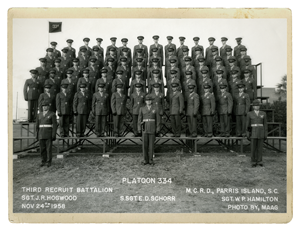

Bill Douglass spent four years at Penn State and Muhlenberg College on a student deferment, but he knew that sooner or later, once he was through with school, the call would come. He figured sooner was better than later, so before he graduated in 1958, with a B.S. in business administration and a wife—he and Joan were married in 1957 during his senior year at Muhlenberg—he enlisted, with a deferred entry date, in the Marine Corps for a two year hitch.

When Douglass earned the coveted “expert” designation with a rifle in boot camp, the Marines decided to make use of his skill. “They asked me if I wanted to be on the rifle team,” Douglass recalled. “The perks were good, so I said sure. I could shoot. When I was a boy I was a fur trapper. I was a hunter too. That’s what we did in the country.”

When he got his Military Occupation Specialty (MOS) and looked up the code in the manual, Douglass found out he was to be a “rifleman/sniper.” Oops. “That was a bad decision. That was not a career,” he said. “You weren’t going to learn anything you could use, and you might not live long enough to use what you did learn.”

Douglass took his problem to the colonel, who decided the Corps could make better use of the young Marine’s intelligence in military intelligence, so he became a “spook.” He also became a second lieutenant—in the U.S. Army, well sort of, but not exactly. But that’s another story.

Somewhere in picking up the credentials to be an intelligence officer, Douglass picked up another two years on his obligation to the military. He was close to finishing that off when, on October 15, 1962, a U-2 high-altitude reconnaissance flight operated by the Central Intelligence Agency came home with photographs of Russian medium-range ballistic-missile launch sites being built in Cuba, ninety miles off the Florida coast, and all bets were off.

“I was on a team set to go into Cuba, capture a Russian technician and bring him back on a raft to a submarine.”

“I was on a team set to go into Cuba, capture a Russian technician and bring him back on a raft to a submarine,” said Douglass, but it never came to that. After thirteen days with the eagle and the bear staring each other down, the bear stepped back, and Russian Premier Nikita Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles from Cuba. “That’s when I got out,” Douglass said. “They sent me on leave, said they were going to reassign me, and I was never reassigned. I was one of those people who got put on leave and is still on leave.” It was time to get back to the plan.

Riding the Esso tiger

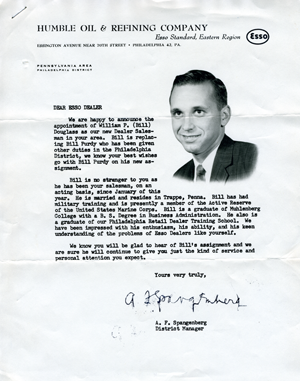

Douglass had never forgotten the offer of the Esso rep he had met when he was in high school to give him a reference. So he called in the marker and applied for a job with Esso.

“The guy who was the regional manager for Esso was a retired army colonel. His trick question in the interview was, ‘What do you think of the service? How well organized are they compared to a business in executing their mission?’ “I said, ‘They’re the best in the world.’ It was the right answer.”

His first outside assignment was as a sales rep in Eastern Pennsylvania. “I was responsible for all the marketing in my territory.” Before long he was an instructor, teaching other reps how to work with service station operators to increase their business and sales of the company’s products. “You had to know how to run a store. You had to work in a store, if you were going to do the job right.”

This was a time when the gas station on the corner was more than just a place to buy gasoline. The sign, “Mechanic on Duty” meant something, and many Americans looked to their local Esso or Standard or Texaco operator to keep the family car running. “We taught these guys how to change a tire, how to fix a flat, how to do a brake job,” Douglass said. “They had to know how to keep people on the road.”

Someone in Esso’s upper management had marked Bill Douglass as a comer, and the promotions, responsibilities and opportunities to succeed, or fail to, came quickly. He ran Esso’s heating oil business in the region before becoming the assistant manager of a small grease and lubrication oil refinery in Pittsburgh in 1968, handling the marketing side of the business. Then, after a short stay in the steel city, Douglass moved west to Albuquerque, New Mexico. “I was promoted twelve times in twenty-one years. I never stayed in one job long enough to figure out if I could do it again,” he said.

Texas was next on Douglass’ itinerary. In Dallas, he took on a different sort of job, manager for marketing investments in the Western United States. “Marketing investments are all the assets it takes to move the product, stations, distribution points, terminals.” He stayed in Dallas for two years before moving to the company’s domestic headquarters in Houston.

Douglass took on several jobs in Houston, from head of marketing strategy to public relations, to government affairs and relations. “We had a government relations rep in every state where we had production, so I worked with the state reps and then got into the federal level, where we had a Washington office,” he said.

The next stop was the Big Apple and Exxon Corp., the international holding company in Manhattan where three hundred people run the multiple companies that make up the Exxon empire. If Douglass could make it there he could…well, you probably know the rest of the line. By that time he had the connections. “If the chairman wanted to play in politics, I had the entrée. My job was to tell the chairman what he could do with certain officials to help us.”

Douglass was breathing the rarified air of business and politics at the highest levels. He had risen very far, very fast, and the next stop for the Douglass-Exxon express was Saudi Arabia, but he didn’t really want to take his family to the Middle East. He had also grown tired of answering to someone else. He wanted to be making the decisions. He wanted to win or lose on his own hook. “That’s when I decided…I was an entrepreneur at heart, I was always an entrepreneur…you only go around once in life, and I just wanted to do it that way.” A different way.

Lone Star State of mind

His heart was set on the Land of Enchantment, but there was no nexus of heart and opportunity. “My heart was in New Mexico, but my wallet was in Texas. That’s what I believed. Now my heart’s here.”

Douglass was looking for a location that Exxon was converting from agent to distributor. He found it in Sherman in 1980. “I got six service stations, two trucks and a facility.” It was an opportunity, but it was also a big step down on the economic scale. It was a long way from 1251 Avenue of the Americas, Exxon’s Manhattan office building, to a grimy gasoline terminal on Montgomery Street in Sherman, Texas.

“It was tough,” said Douglass. “I was here at least fifteen years before I made as much money as I left.” Douglass was forty-four years old, and he was starting over. Not from the bottom to be sure, but starting over all the same.

From his days in high school, Douglass, Inc., had really been Douglasses, Inc. It was double harness hitch all the way. Joan Douglass helped put Bill through college, she followed him through his service in the Marine Corps, and then she moved, and moved, and moved, and moved again as he rose through the Exxon organization. She had had enough too.

“She’s been really patient,” said Douglass. “That’s why I can’t move her out of this house. When we moved to Sherman, we had about two weeks to find a place to live. There were only about half a dozen places in our price range, and the best of the worst was terrible compared to where I had moved her from. It was moving from a big executive place in Connecticut to a small development house in Sherman, which we still live in. “She said, ‘You’ve moved me ten times, and you’re not going to move me again.’ And she meant it.”

Six gas stations and two trucks weren’t going to make it, so Douglass went looking for capital to expand his business. “Howard Hackney of Merchants & Planters Bank loaned on character, and he loaned me a quarter of a million dollars. Now remember, this is when Jimmy Carter was president, so I got to pay 20 percent interest,” said Douglass.

“The interest rate was so high that I had no disposable income. We had a two-wheeler that we used to roll four-hundred-pound barrels around with. It broke, and it took me two days to figure out if I had the $90 to buy a replacement. We rolled the barrels on their edges until I got the money together.”

Early on, Douglass had doubts as to the wisdom of his decision. Exxon had changed the business arrangements, making it more difficult for him to expand his operation, but he persevered. He kept on tossing the dirt in the box, even when they added a slat.

One by one, he added stations and distributorships, picking up businesses when others fell on hard times or decided to quit. “A lot of these guys were World War II veterans, and they were retiring,” Douglass said. When he started in 1980, there were thirteen gasoline distributors in Grayson County; now there are three. Not only are there fewer distributors today, there are fewer brands. Mergers, acquisitions and changing business conditions have brought down the signs familiar to American motorists for decades.

US Hwy 75 and Hwy 82 in Sherman, Texas. (Photo by Stephen Olner)

Gas and Groceries

In 1983, the station at Texoma Parkway and Loy Lake Road burned, and when Douglass rebuilt it, he brought it back as combined service station and convenience store. From that point on, the business model was gas and groceries. “The convenience stores in those days didn’t have fuel,” said Douglass. “So we would go in and put in tanks, pumps, a canopy and fuel. We didn’t buy the stores; we just put in a fuel concession. That’s what we did. That’s how I spent my first ten years.”

By the time Douglass got into the convenience store business, the idea was well defined by the success of 7-Eleven. Despite the Dallas chain’s claim, sung by a cartoon rooster and an owl, “From soup to nuts / That’s why we sing / 7-Eleven’s got everything,” the stores were really a place for those staples Mom forgot to pick up at the supermarket, bread and milk being big sellers, and one supposes, aspirin for the grown-ups who got headaches from the singing rooster and owl. The stores were also stops for kids in search of a soda pop, candy bar or inexpensive toy.

To that mix, Douglass brought gasoline, and all the marketing come-ons associated with gas stations for decades…trading stamps, free glassware and give-a-ways for the kids. “We had all that stuff. We were putting up the signs and hanging the pennants and all that, but we kind of hit the wall with that in 1992.”

The cost of doing business was going up, and individuals could no longer afford to build expensive stores in the locations Douglass and his team had identified as prime locations, even with Douglass Distributing picking up a substantial part of the cost. One of those locations was the intersection of US 75 and US 82 so Douglass decided to acquire the property and build on it himself.

“We designed that store ourselves. We designed the concept right here. We had gourmet coffee, electric doors, canopies that came back from the island. Card readers, we had the first card readers in Grayson County. We put in an automated car wash—the first touch screen car wash. It was a carpeted store, the first carpeted store. Carpet is quieter and cleaner.”

No one had ever seen a convenience store quite like the one in Sherman. Douglass sold French pastries and gourmet sandwiches to go with the high end coffee.

No one had ever seen a convenience store quite like the one in Sherman. Douglass sold French pastries and gourmet sandwiches to go with the high end coffee. When Starbucks was just starting to expand, North Texans were sipping high-end brew at the Lone Star Convenience store in Grayson County.

The store attracted attention, envy and admiration from others in the convenience store business all over the country. In 1997, the store was named Convenience Store of the Year. Douglass followed that award with another a few years later for the store in Van Alstyne. The mix of fast gasoline, fast service, and now fast food was registering with customers. At one time or another, his stores have housed Burger King, Baskin-Robbins, Subway, and Dickey’s.

Douglass will admit that some of his ideas have not quite panned out. The French pastries and salmon sandwiches were a little ahead of the curve for the doughnut-and-burger tastes of North Texas, and his most radical departure from convenience-store and fast-food conventions never got off the ground.

A few years ago, he planned to build a store with the first fast-but-elegant dining concept anywhere at the intersection of US 75 and FM 691. The idea was top-class food, served in an atmosphere of casual elegance for travelers looking for more than a hamburger and a Coke.

The idea fell by the way when Sherman went wet. “Its claim to fame was that it would have been the closest source of alcohol to Sherman, and that would have helped support that elaborate dining idea. We had a fabulous, fabulous design for that place. It would have been the most elegant facility in the county.”

The original plan called for a butterfly atrium. “We were going to get the butterflies from Costa Rica,” said Douglass, “but we learned that the Department of Agriculture had all these requirements about the butterflies. We had to have all kinds of elaborate measures so the butterflies couldn’t escape, and when they died, we had to dispose of them like medical waste. And another thing the people in Costa Rica didn’t tell us this until we had $80,000 invested in this thing, we would have to keep the temperature at 80 degrees and the humidity at 80 percent.

“Well that killed the butterfly thing, and it killed our enthusiasm for the elaborate thing. We were trying to build a destination. We had a $1,000,000 in the ground and $140,000 in the design, but it just wasn’t going to work anymore.” Douglass eventually got his money out of the property, but he still thinks wistfully about those butterflies. Sometimes it is risky to think so far outside the frame.

So, can Sherman and Denison expect any great new advancement in convenience stores in the immediate future? Probably not. “Right now, with our population density and the convenience store density, it’s impossible to build a facility that would pay out. Here I mean, not in the high growth areas.”

Slower than heralded growth in Grayson County, the big boom always seems to be just down the road a piece, which means that there are few opportunities for the almost daring innovations that Bill Douglass thrives on. Doesn’t that mean no more dreams of butterflies in the dining room? Not really, he’s just adjusting his sights.

“We’re changing our business model. We’re over built. We have eighteen new restaurants in the last five years, but the town has grown by only a few thousand people. With the big box retailers, the grocery business is probably overbuilt. Everything here is saturated for the population. So I don’t need to build here. All I’ve done is remodel.

“But we’ve expanded our business. We supply the City of Dallas with oil products. We are in the bio-fuels business. We buy it, and we blend it right here in Sherman. We put in a $280,000 facility last year. Its growth will become explosive whenever the price of crude goes up.

“Is it as much fun? No, retail’s more fun, big fun, but that’s the world.”

Wow! What a great story. Bill Douglass, is the kind of guy that would LOVE a project like the NEON TIKI TRIBE (Super Heroes for kids, that TEACH them real life lessons). I hope I get to meet him someday. Way to go Bill! Thanks for your service to the country too! Sincerely, “Tikiman” Greg Devlin

So glad to read this article. Very interesting to me…I really enjoy the pictures of Bill Douglass and very happy for all of your family success.