This article appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of Texoma Living!.

by Leona Miller

Unknown to most of us there is a great debate rising over the true lineage of the frozen treat we casually call ice cream. It’s not a recent debate—it’s been going on for about 400 years—more or less.

Without going into all of the myths and legends, it’s easier to just talk about the things we know to be true based on written history. That is, not history as written and approved by the International Association of Ice Cream Manufacturers (IAICM). The IAICM is a trade lobbying group headquartered in Washington, D.C. Their job is to perpetuate the official ice cream story—that once again, I’m not going to belabor.

Did I mention there’s a course on ice cream history at the University of Wisconsin?

Most ice cream scholars (there are some you know) seem to agree that the frozen dessert we know today began in the 1600s. It probably evolved from flavored ices, though no one is sure how exactly.

It is written in more than one place that King Charles I of England had served ice cream as a staple at the royal table. Legend Alert: The rumor is that the King swore his chef to secrecy on pain of death so that no other royal types could have the recipe. When Charles I was beheaded in 1649 the kitchen staff started talking and soon nobility across Europe discovered the secret of “créme ice.”

Historian and scientist Chris Clarke, in his 2004 Royal Society of Chemistry monograph The Science of Ice Cream links the development of ice cream to the evolution of refrigeration.

Clarke posits that the discovery that dissolving salts in water produces cooling (there’s the chemistry angle)— and the fact that mixing salts and snow or ice cools even further in the mid to late 17th century— allowed cream to be added to flavored ices.

By the 18th century “iced creams” were widely enjoyed by the upper class on both sides of the Atlantic. Several recipes appear in a 1700 French cookbook, L’Art de Faire des Glaces, and the American colonies had ice cream on the menu.

Thomas Jefferson had a personal recipe for vanilla ice cream. George Washington reportedly paid a $200 bounty for a specific recipe, and James and Dolly Madison served ice cream at their second inaugural ball. The effort to serve ice cream was monumental. Servants stood over large bowls of ingredients, sitting in larger bowls of salt and ice, shaking the larger bowl while continuously stirring the smaller.

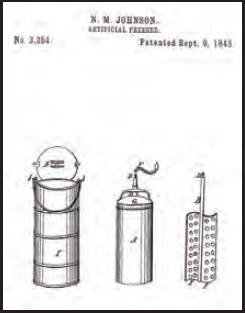

In 1843 a Philadelphia, Pennsylvania housewife named Nancy M. Johnson, designed and patented (U.S. Patent #3254) the first hand-crank ice cream maker. By turning the crank a metal cylinder filled with the ingredients with agitated in a bed of salt and ice until the mix was frozen.

Johnson’s design was purchased by William Young, who filed a revised patent and who routinely gets credit for the device. Young credited the inventor by calling the machine the Johnson Patent Ice-Cream Freezer.

Now, on to the ice cream cone legend. With all due respect to the St. Louis, Missouri Chamber of Commerce, the edible waffle cone did not first appear at the 1904 World’s Fair in your wonderful—and very humid—city. And aren’t you the same guys who touted for decades that you also introduced the hot dog bun and hamburger bun to the world?

A New York immigrant, Italo Marchiony, filed a patent for the waffle cone mold/cooker in 1903. He had in fact been serving lemon ices in these cones from his push cart since 1896.

Records of the time document no fewer than 50 ice cream stands at the St. Louis fair that summer.

It may hard to imagine, but there is also controversy over the origin of the ice cream sundae.

Sundi, Sondhi, Sundae!

On July 8th, 1881, a customer in druggist Edward Berner’s ice cream parlor asked for a ice cream soda. It was Sunday. It was against the law. As a compromise Berner put the ice cream in a dish and poured the chocolate on top.

Now this is a critical point: At that time chocolate syrup was only used to flavor ice cream sodas. Berner’s concoction was not only heretical, it was radical.

Today there is a replica of Berner’s ice cream parlor in the Washington House Hotel Museum in Two Rivers, Wisconsin. So how is it that Ithaca, New York also has a museum that hails the ice cream sundae as a local concept?

Ice cream historians—there are a few—believe there is overwhelming evidence to award the “first sundae” award to the Platt and Colt’s drugstore in Ithaca.

Chester C. Platt—as the story has been documented by in person interviews of the time—was serving up a dish of just plain vanilla ice cream for his customer, Unitarian Reverend JohnScott. He added a topping of cherry syrup over the scoops, then adorned the whole thing with a candied cherry.

The next week Platt’s Drugstore began advertising the new creation as a “Cherry Sunday, a new 10-cent ice cream specialty.

In Evanston, Illinois they never claimed to have invented the ice cream sundae—just the name.

Sometime in the late 1800s the city fathers outlawed the “Sunday Soda Menace.” Leave it to American ingenuity to find a way around just about anything. Garwood’s Drugstore wasn’t willing to give up the revenue from selling ice cream sodas on Sunday, so they just removed the offending fizzing soda—which it seems was what all the fuss was about.

There is general consensus that the name “sundae” comes from the days when the “Blue Laws” prevented ice cream sodas from being served and consumed on Sundays. Religious authorities felt they were too “frilly,” and added them to the banned list of items that could not be sold on the Christian Sabbath. Other items included pots, pans, washing machines and liquor.

With the sparkling, fizzing soda extracted from the ice cream soda—and thereby avoiding the wrath of God—the sundae was born and the Blue Laws sidestepped.

The treat has been referred to as a “sundi,” sondhi,” and the more popular “sundae.” All this to avoid naming frivolous dessert after a Holy day.

Let’s let someone else sort all this out. As for myself, I’m headed over to Braum’s.

This article was researched using a number of references including “1888s: Historical Event/Fact, by Tamara K. Gross; “A Month of Sundaes: Ithaca’s Gift to the World,” by Michael Turback, Red Rock Press; “Chocolate, Strawberry, and Vanilla: A History of American Ice Cream,” by Ann Cooper Funderburg, published by Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1995.