Sometime after the impoundment of Lake Texoma began in the spring of 1944, when waters that had started in the high county of Eastern New Mexico and wandered lazily down the Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red and into the river proper began to spread out behind the dam at Baer’s Ferry, an old man came to the shore of the rising lake with a reporter from the Denison Herald.

See more photos related to this article. Scroll to the bottom of this page.

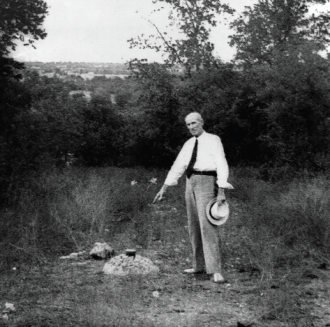

The man stooped down, picked up a pebble and tossed it into the water, then watched in silence as the ripples spread in concentric circles and disappeared. Then he turned and, more to himself than to his companion, said quietly, “Well, that’s that.” For seventy-five year old George Moulton, the man who had sat down and written the letter that started it all, his work was finished; he died on Dec. 14, 1944.

George Moulton wrote a letter

It was March 1926, and he had just come back home to Denison from a trip out West, where people were talking up an idea for a great dam on the Colorado River near the Arizona-Nevada state line. Moulton’s thoughts were not on the Colorado, however, but on a water course closer to home—the Red River of Texas.

The Red had the reputation as a mean river. Docile most of the time, given to dry spells that made it all but unnavigable above the rapids at Alexandria, Louisiana, in flood it ran hard and unchecked for 1360 miles from its headwaters on the Llano Estacado to its confluence with the Mississippi, 341 miles above the Gulf of Mexico. When aroused, it was a river of ripping currents, dangerous eddies, and quicksand that could swallow a man or an animal.

Moulton was the stepson of Colonel J.B. McDougal, of one of Denison’s enterprising business tycoons. He had grown up in Denison and had seen the devastation the Red could bring when it was on a tear. So that spring, with thoughts of dams and flood control projects in his head, he sat down and wrote a letter to Oklahoma congressman Charles Carter requesting a collection of topographic maps of the Red River valley.

Moulton was not an engineer, but he understood the concepts involved in building a dam, and he had a more than passing knowledge of geology to bring to his study. When the maps arrived, he studied them carefully and translated the thin contour lines into a location for a dam on the Red River at a site called Baer’s Ferry, four miles northwest of Denison. When the project took root a few years later, the Corps of Engineers would spend months examining the terrain and come to the same conclusion as Moulton. Baer’s Ferry was the spot.

“People thought I was crazy,” Moulton said later. “Even my friends ducked out of the way to escape my persistent evangelizing.” He wrote hundreds of letters to congressmen, government officials—anyone who might have a say in making the Denison Dam a reality.

It seems it was always the “Denison Dam.” Perhaps at first it was just to be a dam at Denison, but it soon became the Denison Dam, and no other designation shows up in the newspaper accounts of the project.

On September 26, 1930, the dam project got a significant boost when three hundred delegates of the East Texas Chamber of Commerce gathered for a convention at the Y.M.C.A. in Denison. The influential group had gone on record in support of the project a few days earlier at a meeting in Sulphur Springs, but the Denison conference brought together for the first time many of the players whose support for the effort was vital.

At the head of the list was the congressman from the fourth district of Texas, Sam Rayburn of Bonham. Hatton W. Summers, the house member from Dallas, was on hand also, and so were representatives from Texas Power & Light and the Corps of Engineers office in Vicksburg, Mississippi. George Moulton was there to talk about his idea for the dam, and Dr. A.W. Acheson of Denison, who had joined Moulton as one of the chief proponents of the plan, spoke with zeal of the expansion and utilization of the natural resources of the Red River Valley that would follow the project’s successful completion.

All the while, Moulton’s letter writing campaign continued. He even wrote to Henry Ford, trying to interest the automobile tycoon in the project. For his time and a three cent stamp, Moulton got a short reply from Ford’s secretary. “Mr. Ford thanks you for your inquiry, but at this point in time he is busy in the automobile business.”

The climate for the dam project brightened with a change in the Washington political scene on March 4, 1933. Herbert Hoover moved out of the White House and the governor of New York, Franklin D. Roosevelt moved in. FDR’s new vice-president was a Texan and former speaker of the house, John Nance Garner of Uvalde, and one of Roosevelt’s strongest supporters in the House of Representatives was the man from Bonham, Sam Rayburn.

The county was deep in the Great Depression, and as the new president searched for ways to stimulate the economy and bring hope where there was little save despair, the expenditure of public money for public works started to gain favor. George Moulton added a new address to his letter writing campaign, and the resident of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue began getting letters with a Denison, Texas postmark.

“Best town by a dam site.”

1936 was an election year, and FDR was barnstorming the country drumming up votes to beat Alf Landon of Kansas and garner four more years in the White House. On June 1, his campaign train pulled into Denison, and the president offered a few words to the five thousand plus who had come down to greet him.

“You may not believe it, but I know quite a good bit about you,” said the president. “I may know more about your geography than even you know. Thanks to Sam Rayburn, I know about your problems. I know that there are thirty-one thousand farms in this region, and that only seven hundred of those farms have electricity. We want every one of those farms to have light.” George Moulton’s letters were beginning to make a difference.

Before the year was out, Captain Lester Rhodes of the Corps of Engineers come to town and opened an office in the Citizens National Bank building. With little fanfare, the engineers began poking around, doing tests and looking things over. A few months after they had arrived, they were gone.

In 1937, the Red River Valley Association came into existence in Shreveport, Louisiana, and at a meeting of the group, Congressman Rayburn led a contingent from Denison who were there to boost the dam. Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana announced their support, and perhaps for the first time, people began to see that there was possibility where before there had been only dreams.

The army came back to Denison in September 1938. This time Captain Lucius B. Clay led the engineers. Clay was a man who got difficult things done, as he would prove a decade later when he led the airlift that kept the Soviets from starving the allies out of Berlin, but in 1938 Clay’s job was to draw specific plans for a dam at Baer’s Ferry, and this he and his team did. But plans are only plans. It takes money to turn plans into the reality of concrete and steel, and for nine months Denison waited for news of funding from Washington.

One would like to believe that someone dashed into the offices of the Denison Herald on June 29, 1939, and shouted “Stop the presses!” It probably did not happen that way, but nevertheless a special edition of the paper was soon on the street, bearing the news that congress had passed a $5,000,000 appropriation to start construction on the dam.

Denison exploded as hundreds of people took to the streets in an unplanned parade. It was going to happen. George Moulton’s dream was going to come true. There were as many reasons for celebrating as there were people in the crowd, but you would have been hard pressed to find anyone who did not agree with the sign Dr. E.L. Hailey hung on his car: “Denison, the Best Town by a Dam Site!”

Getting started

The impromptu party that Denisonians cranked up to celebrate the appropriation of funds to start construction on the Denison Dam was followed by a more formal affair on August 22. The official purpose of the festival was to honor Congressman Sam Rayburn for his part in bringing the dam project from dream to reality.

Hundreds of visitors and scores of dignitaries from Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana came to town for the event. Main Street was festooned with red, white, and blue banners, and patriotic bunting decorated the store windows and awnings. Things started with a lunch at the Hotel Denison for the principal guests, and then at four, the crowd gathered for speeches in Forest Park, followed by a big barbecue.

Rayburn spoke to the thoughts of all assembled when he noted, “The waste of Red River has been a terrific loss. The mighty and ruthless flood, when harnessed behind the dam that will be built, will not only preserve life, homes and lands below it, but will provide a source of power that will bring to the farmers and communities throughout a vast area the great energy of electricity now so necessary to modern life.”

Oklahoma congressman Phil Ferguson praised the project too, and that put him at odds with his governor, Leon Phillips, who vehemently opposed it. The keynote address came from Texas senator Tom Connally, and when he and the other politiciansfinished, the crowd lined up for three thousand pounds of Texas brisket.

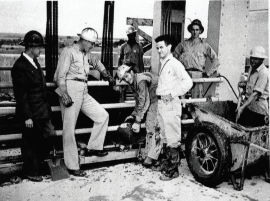

Actual work on the dam had started nineteen days before the Rayburn festival, when the first tree was felled on the dam site. In time, thirty thousand acres would be cleared, with some of the work done by German prisoners of war from Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps. The POWs were captured when British and American forces defeated the Germans and Italians in North Africa, and many were sent to stockades in Texas. The Geneva Convention required prisoners be held in a climate similar to where they were captured, and the American Southwest seemed a suitable stand-in for the deserts of Libya, Tunisia, and Morocco. The first Germans arrived in Texas in April 1943, and in short order, camps were set up in Tishomingo and Powell, Oklahoma, for prisoners who volunteered to work on the dam project. They were paid eighty cents a day in canteen vouchers.

On September 22, 1939, the Katy brought a load of earth moving equipment to the dam site over a newly constructed spur track. The heavy equipment bit into the ground on October 2, and the construction of the dam proper was underway.

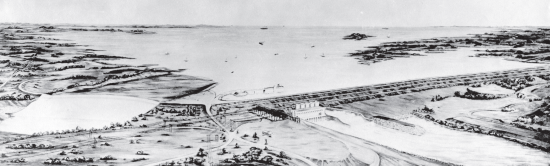

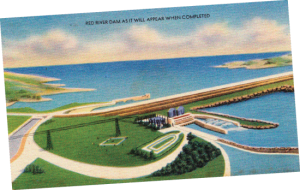

First came the great concrete and steel intake-outlet structure and powerhouse on the Texas side of the river where it rested on Goodland limestone and Trinity sand. When that phase of the project was completed, crews laid a system of huge tubes beneath the earth to channel water from the lake to the gates and the powerhouse. Meanwhile, work had started on the earthen embankments reaching out from both banks of the river. The construction of the embankment, most of which would be in Oklahoma, was the largest project of its type ever undertaken anywhere in the world at that time.

When the embankment was finished, save for the gap through which the river still ran, a coffer dam was constructed to divert the Red from its old natural channel through the new man-made intake structure. Then the workmen filled the gap in the embankment, and the river was no longer free to wend its way to the sea.

The Baer’s Ferry site, 751 river miles from the Mississippi, lay at the narrowest part of the Red River Valley below the Washita River. On the Texas side, the banks of the Red were high, 150 to 200 feet, while across the river they stood 30 to 40 feet and then leveled off for more than a mile before rising another 50 feet. More than a dozen spots had been considered, but the engineers always came back to the site first identified by George Moulton years earlier.

Two companies, the Gordon W. Condon Company and the John Kerns Construction Company, set to work excavating the site for the intake- outlet structure and powerhouse. With 3,000,000 cubic yards of dirt to move, they worked two shifts, and then at 11 p.m. each night, sub-contractor R. G. Aldridge took over the dig. No all-illuminating floodlights were available in those days, so smaller lights were stuck on earth-moving equipment and trucks and anywhere else that seemed advantageous.

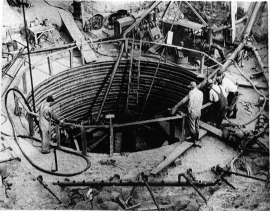

When the site was ready, C.F. Lytle Construction Company started work on the guts of the dam and the powerhouse. Over the Katy spur, on May 9, 1940, came the first thirty cars of crushed stone aggregate from Stringtown, Oklahoma, and at 1:10 p.m. on May 21, the first concrete flowed into the forms to make the footings for the southwest corner of the huge block that would encase the eight, 20-foot in diameter conduit tubes.

The crews poured concrete every day in two shifts, from 4 p.m. until midnight and from midnight until 8 the next morning. During the day, a third shift built forms. The volume of concrete used for the structures would have built a highway ninety-one miles long.

While Lytle crews worked on the structures, the powerhouse and eventually the spillway, the Guy F. Atkinson Company of San Francisco started on the embankment. It was like building a mountain.

Work started on July 31, 1940, when trucks dumped the first loads of dirt near the center of the dam. Hauling the dirt were seventeen of the biggest single-unit trucks ever seen anywhere. They were assembled on a line at 619 W. Main in Denison by the Knucky Truck Company from parts shipped in from all over the country.

As the dirt went down, it was compacted by giant rollers pulled by bulldozers. The embankment is dirt, all dirt and nothing but dirt, save for a protective section of steel beams driven into the ground near the Burn’s Run area. There, the sandy soil is water permeable, so the steel was added to prevent seepage.

On October 18, 1943, the last load of dirt—17.5 cubic yards worth—went on the pile, and the embankment was completed. At 165 feet high and more than a mile long, it was the largest earthen dam ever built up to that time. A press release from the Corps of Engineers put the embankment project into perspective. “Denison Dam was a major step in the evolution of the modern embankment dam. The rolled earth feature of the Denison Dam was unique. Its completion established an engineering approach that became the standard for construction of most subsequent earth filled dams.”

Even as the construction progressed, there were efforts to bring the entire project to a halt. Chief instigator was Oklahoma governor, Leon C. Phillips. Years before, one his predecessors, “Alfalfa Bill” Murray had derided the idea of a dam on the Red as “the biggest folly ever proposed.” Governor Phillips was no better disposed to the idea.

He turned to the courts, arguing that the project would destroy 100,000 acres of Oklahoma land and remove it from the tax rolls, that the state was not guaranteed payment for damage to roads, and that property owners had been short changed. He said the dam would change forty miles of the state’s boundary with Texas, and besides, the whole thing was unconstitutional and a bad idea to boot. It was “everything but the kitchen sink” litigation at a high level.

Twice the question made it to the United States Supreme Court. Then on June 2, 1941, the court figuratively told the governor to take a hike, declaring that “the project was constitutional and that the federal government was not invading state rights.” The justices may have had concerns that agreeing with any of the claims might imperil similar flood control projects all over the country, or perhaps they had simply grown tired of the same old objections that had been raised by naysayers going back to battles over the Tennessee Valley Authority.

But there were more problems than just the sniping of Governor Phillips. In the area slated for inundation by the water of the Denison Reservoir—it was not Lake Texoma yet, that would not become official until September 13, 1944—was the 11.5 square mile Cumberland oil field near Madill, Oklahoma. Something had to be done to protect the field. The solution was two dykes to keep the fields dry.

And then there were the relocations. Many things had to be moved, or rebuilt. There were nine miles of new track to be laid for the Katy between Pottsboro and Sadler; in Oklahoma there were bridges to be built and track to be re-laid between Ligrett and Platter Flats, and another bridge and track project south of Ravia. US Highway 70 between Durant and Madill had to be rerouted over a new bridge, and Oklahoma Highway 99 needed seven miles of new construction. Three towns, Hagerman, Texas, and Alyesworth and Woodville, Oklahoma, were swallowed up by the rising waters of the lake.

But by far, the biggest removal operation involved the disinterment of bodies from three thousand graves in forty-nine cemeteries. The Corp of Engineers built eleven new grave yards to accommodate the removals and, if the relatives requested, moved remains to other, existing cemeteries. It took almost a year to carry out the graves relocation. The public was barred from the work areas and workmen held to strict standards of decorum.

With the relocations completed and the gap in the dam filled in, the coffer dam was dismantled, and on January 6, 1944, impounding the muddy red water of the river for the reservoir began. It would take fifteen months, until March 15, 1945, for the lake to reach its normal elevation of 617 feet above sea level.

Well, that’s that.

The official dedication of the project was July1, 1944, and the principal speaker for the event was Congressman Sam Rayburn, now Speaker of U. S. House of Representatives. It was two minutes past the scheduled 9:45 a.m. starting time, when Chief Warrant Officer Frank Purnell cranked up the Perrin Field Band with a rendition of the “Over There Fantasie” before booming out the four ruffles and flourishes followed by “The Stars and Stripes Forever” that protocol specified for the speaker of the house when he arrived.

The newsreel cameras rolled, and Rayburn and Oklahoma Senator Elmer Thomas posed for pictures with a tape measure. The ceremony lasted for two hours and thirty-three minutes, but the audience, which, perhaps because of the heat, was considerably less than the twenty-five thousand that had been anticipated, clapped and cheered at the right places, and was suitably awed by the structure.

And so it was done. The river that for an eon had run free had been brought to heel by a great man-made mountain of earth and concrete, its power to destroy all but eliminated and redirected to the service of the land though which if flowed.

This article appeared in the August 2010 issue of Texoma Living!.

Note: Material for this piece was augmented from a monograph written by Fran Higginbotham in 1971. Photos were provided courtesy of the Red River Historical Museum.

I think it’s time for some sort of memorial to George Moulton. Admittedly, it took powerful work by connectd politicians to get the dirt flying for the Denison Dam, but it was George Moulton who pulled the idea out of his imagination to build the dam and initiative to badger citizens and local, state and federal politicians to get the necessary positive legislative traction. He’s received very little public recognition. How about a statue with him pointing to the spot for the dam, a day honoring him, naming the library after him, anything ? Just sayin’.

I believe it was my grandfather George W. Condon who did excavation work, not Gordon W. Condon.

I have recently acquired a set of Original Plans for the Intake Structure and the Power House dated 1939. They had been kept in the same Family since 1939. They belonged to a man named Milo Stych who was an Engineer on the Project. I wanted these Plans because I live very close to the Site and I drive by it almost Daily. I’d like to send a Thank You to Traci.

My dad, W. M. Bradburry, also worked on the dam.

we lived in Bosier City and my father worked on a dam near Shreveport, La.

I would say this was in 1940 or 1941.

Just wanted some more information. He was L.L. Odom, 3rd. we moved there from va., where he worked on a dam also. Just interested to find out more. thanks, Peggy Kellar

I’d check with the Corps of Engineers office in Tulsa.

I have always heard my Dad talk about working on the Denison dam with the WPA. I have been unable to find any records do they exist? I don’t know how long he worked on it or even the exact time. His name was George Morrison. Any ideas on how to find out about the records? Thanks.

My grandfather was GEORGE W. CONDON, not GORDON W. CONDON, of the George W. Condon Construction excavation company you cite in this article.

My Grandfather Jack Sudderth was a worker on that dam. He had something fall on him and it broke his back, I’m not sure what fell on him. He was crippled for the rest of his life. I would like to find more information on the building of this bridge.

I am looking for pictures concerning the construction of the dam (Lake Texoma), powerhouse, intake-outlet works, and such. As a child I remembered touring the powerhouse but of course there are no tours these days. There were pictures of various sturctures being built on the walls of the atrium overlooking the powerhouse floor. I can only find 4 pictures (one aerial shot of the intake-conduit tubes-outlet works and three concerning the powerhouse) from online sources but surely there are many more available for such a large project. Any help would be appreciated. I am a bit of a history maven. Dave

My father Archiebald “Archie” Gardner worked on this dam. We came to Cartwright when I was two years old in 1939 and I lived there with my parents and siblings until I was 18 years of age. I remember many stories about the making of the dam and also remember Greman prisoners that worked on this site. My brother Edward and I would watch them as they built the smaller spill ways that ran from the highway on the dam to the area below. One such prisoner showed us a photo of his children. They appeared to be our age. He spoke to us but we didn’t understand what he had said but I think he wanted us to know he had children also. There were also several buildings located near the power plant that had something to do with the prisoners.

I want to thank you for this article I throughly enjoyed it. Well done!

This web site made my day!

Your photo labeled “A granite monument notes the border between Texas and Oklahoma” is indeed a photo of the stone that noted that border, and it stood north of Denison, just south of the old iron bridge. The photo looks like it was taken in the “dead of winter”, possibly when first erected about 1936, a WPA project. Several photos have been gathered from different family albums which place the location close to the first turn toward the south such that both the parallel railroad and the highway could make their connections in Denison – as seen in USGS maps. My family shots were made about July 4, 1940. We also have recent photos of the “stone” that presently resides on the south end of the Denison Dam. The face lettering, blemishes in the stone faces, and base ledge-rock pieces are distinguishable. Was the stone that’s now on the Denison Dam moved there from the place where 91 previously crossed over a toll bridge west of the location of the dam? That was an area that was to be drowned as the Lake Texoma waters were impounded. I would love to know.

The famous parade and Dr. E. L. Hailey’s sign is featured in a Denison Herald print that may be seen at: http://www.swt.usace.army.mil/recreat/laketexoma/webpagetexoma/historical/

One postcard featuring the “stone” north of Denison and the slogan “Best Town In Texas by a Dam Site” is possessed by a friend of mine in Denison.

Can you confirm if the photo of the “stone” near the state line was taken shortly after erection in about 1936? … Wow! This is great!

Wonderful work!